Throughout human history art has been described in as many ways as it has genres:

harmony, life distilled, thought expressed through form, a habit-forming drug, and even a revolt and protest against extinction. And, to be sure, art has had a deserved and important place throughout human history. But does it have a place in your portfolio?

David Stevenson of The Financial Times seems to think so. In espousing new artistic talent, he says that “buying emerging art is the equivalent of investing in frontier market equities.”

And he’s not the only one. Around the world investors are speaking with their hard-earned dollars. “We have noticed increased interest in art being acquired for investment purposes from new buyers to the market.

This new breed of collector is being attracted by the allure and prestige of the potential financial gains art can bring versus pure aesthetic appreciation,” says Harvey Mendelson of the art advisory firm 1858 Ltd.

That would explain the upsurge of new art marketplaces and offerings in recent years. As a traditional investor, you might not have heard of the segment’s smaller entrants such as Artfinder, Saatchi Art or Expertissim to name a few, but you’ve certainly heard of Amazon and Ebay, who’ve both recently come out with dedicated marketplaces for the purchase and sale of art.

Joining this prestigious array is the new online marketplace ArtBanc Trading Platform. ArtBanc markets their new offering as a Trading Platform for fine art, jewelry, sculpture and photography in the $20,000 to $2 million-price range.

What they believe sets them apart is seller access to global buyers at vastly reduced commission rates (5% to 8%). They’ve also done away with buyer's premiums and incentive fees. These combined transaction fees sometimes cost sellers using traditional markets like galleries and auctions upward of 30%.

Beyond the prestige

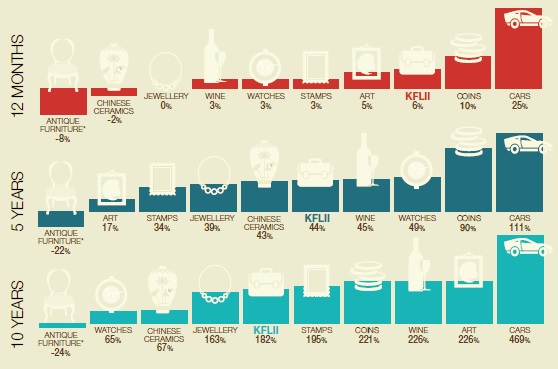

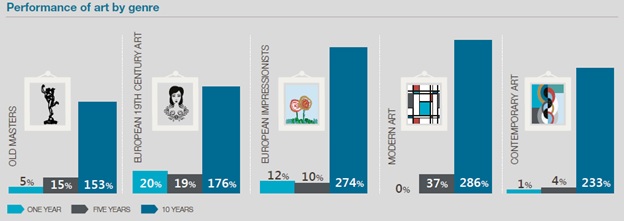

But what is it about the art market that’s drawing in this new class of investor (pardon the pun)? Well, beyond the prestige, sound art investing does deliver quite a return. According to Knight Frank’s 2014 Luxury Index Report, art’s 10-year performance as an investment asset is 226%, beating other exotic alternative assets such as wine, coins, stamps, jewelry and antique furniture.

In fact, the only exotic alternative asset that bests it in a 10-year period is cars, with an overall return of 469%. Furthermore, since art prices don’t move with the stock market or interest rates, investors can use art to balance their portfolios without much added volatility.

Source: Knight Frank's Luxury Index Report 2014

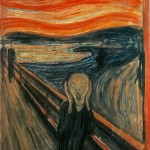

Needless to say, you can always proudly display it in your home, too. That is, unless you happen to be investing in the grotesque--a hot item these days, mind you. Last year, it was a Francis Bacon triptych that smashed the world record price for an art auction, selling for $142.4 million. Who did Bacon take the record from? None other than Edvard Munch and his famous Scream painting--wouldn’t that be quite the buzzkill in your living room?

But what about those of us who don’t fit into the narrow range between Rockefeller and Rothschild (and not just alphabetically speaking)? Is there room for the every-day investor to take part in this elite market?

Funds instead of bids

Up until recently, it was an all-or-nothing sport. You either outbid the person beside you or you went home empty handed. Sensible enough, it would certainly be impractical to lay claim to one share of the Mona Lisa. But relatively recently there’s been a new way to invest in the art market. Funds.

An art investment fund works just about the same way as a traditional investment fund. The fund buys up art--either pieces it believes are currently undervalued or “blue-chip” works by artists that offer reliable returns--and then attracts investors to buy shares in the fund itself. Some funds focus their attention on art from a certain geographic region, others on a certain style or period, and others still on specific mediums such as photography.

This makes the lives of individual investors easier, since now they can invest in art without many of the usual trappings such as illiquidity, lack of buyer security or knowledge, and the actual physical handling of the paintings themselves--no small feat.

And these new funds are popping up everywhere, holding an estimated $2 billion worldwide in total assets according to the Art Fund Association. But the fund investment life isn’t all pink Van Gogh roses.

Regulating a nonexistent market?

Critics have levelled accusations that there is a distinct lack of regulation in the art market, and they’ve even accused some wealth managers of exploiting this opaqueness to bid up the valuations of works in their funds.

This highlights some of the broader problems involved in investing in art. Transaction levels are low, after all, and this makes for a palpable lack of transparency in the market as compared to traditional investment classes.

Indices that track art prices only capture a small cross-section of overall trade, and even then they are only calculated on, at best, a quarterly basis--often it’s as little as annually. Auction houses, for their part, do provide figures on art sold at auctions, but even that only accounts for roughly half of the market.

Meanwhile, galleries and private dealers have little reason to shed light on their dealings with notoriously private and wealthy collectors. As Melanie Gerlis, art market editor for the Art Newspaper, puts it, “If one work by Manzoni sells for $20 million but another doesn’t sell at all, it doesn’t make the average price for a Manzoni $10 million. There’s no such thing as the art market--there’s just a lot of individual paintings.”

Our new asset class’ growing pains don’t end there. A 226% return might sound irresistible, but alternative assets such as art generate no additional dividend income or coupon Payments , unlike their traditional security brethren. Once you compare these returns to traditional assets with reinvested dividends and coupon payments factored in, you are left with a less attractive return.

Furthermore, changing tastes mean that you never really know how your darling abstract will hold up in a few years’ time. The pernicious mood swings of the collective consciousness might mean that the market may very well turn on its heel one day and say, “On second thought, Rothko, that just looks like colorful squares.”

Source: Knight Frank's Luxury Index Report 2014

Another problem is that alternative investments are prone to bubbles. There was a big bubble in stamp collecting in the 70s and a classic cars bubble in the 80s. More recently, prices of wine shot up thanks to speculation on Chinese enthusiasm. This bubble burst, too, sure as an overpriced bottle shattering on the cold hard ground of reality. Even now, there are constant questions of whether the art market is in the throes of a bubble. Many believe it to be the case, but others think that the market is too fragmented to be at risk. Certainly, though, they see particular artists exhibiting bubble-like behavior.

Finally, art isn’t exempted from inheritance tax like some other exotic alternative asset classes such as classic cars and some wines. While not particularly fair, art doesn’t meet the requirement of being a “wasting” investment like these other classes. Though, if you’re really interested in passing your collection on to your children tax-free, you might be able to do so by instructing them to preserve them and allow public access.

Bottom line

In conclusion, approach with caution, otherwise it’s your portfolio that will be screaming like Edvard Munch’s preeminent work. For the many benefits of investing in art, there are just as many pitfalls, so be sure you know what you are doing and that you do your homework properly. Take a page from the best pioneers of artistic creativity and know the basics before taking too many creative liberties.

And sure, there are some who will tell you that you should only buy art because you love the piece, and that buying art as an investment is to totally miss the point. While there might be some truth to this statement, let's be honest, Ben Graham has been saying the same thing about stocks for nearly a century... try telling that to the stock market.